Morpheus: World Models to Generate 2D Games

World models are all the rage now. From General Intuition's oversubscribed seed round to Yann LeCun's new startup AMI Labs to NVIDIA's COSMOS, companies are taking massive bets on these models to improve autonomous driving, environment simulation, video games, robotics, synthetic data generation, and more. In my last blog post, I talked about using state-space models for game generation without an engine but in this post, I want to focus more on world modeling as an alternative approach for generating video games autoregressively.

In the past year, we've seen more and more evidence (Genie 3, Odyssey-2-Pro, Runway's Gen-4.5) that we're accelerating towards a future of "generative" AI games. Imagine an almost experimental playground where people can design, style, and customize games/films with infinite precision without the necessity of an underlying engine. This is not to say traditional game engines or filmmaking are going away any time soon, but I sincerely believe world models will have orders of magnitude of an impact on the gaming and film industries, especially as long-horizon generation becomes feasible.

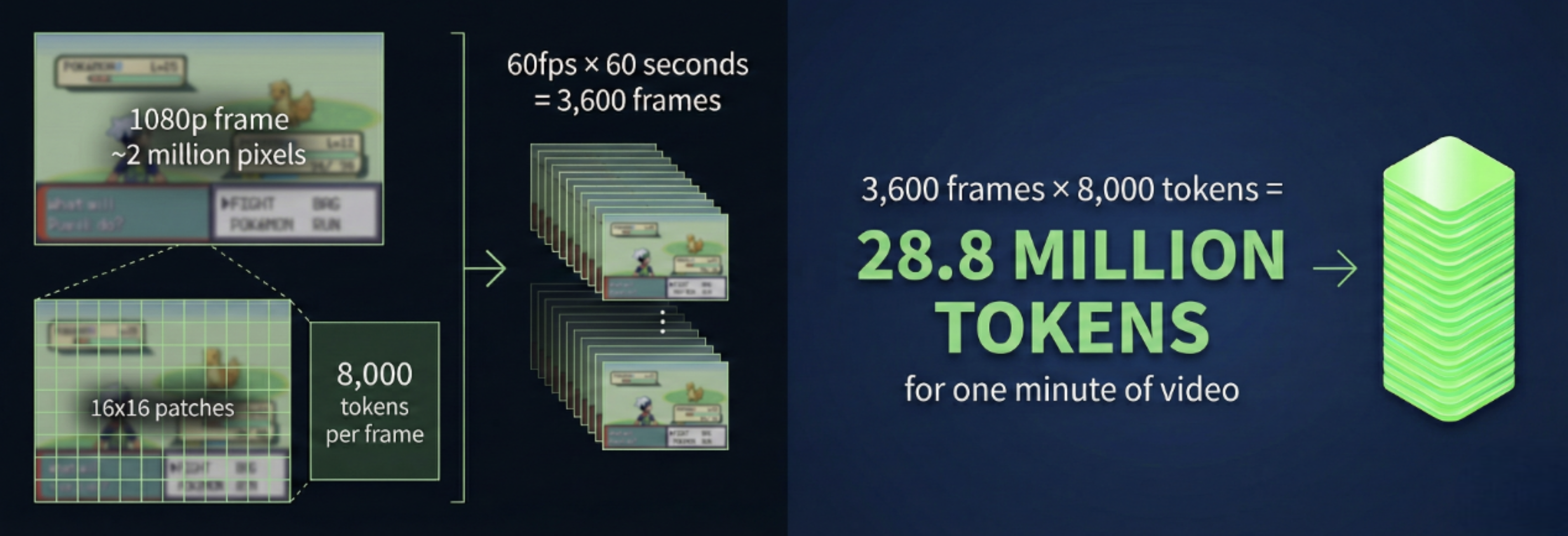

On my previous point, it's no secret that video/world models are (currently) horrible at long-context generation, partially because current VLMs are glorified image models (more on this soon) but also inference/generating frames is ludicrously expensive. To best illustrate this let's start with a 1080p video (each frame is ~2 million pixels) recorded at 60fps for 60 seconds. Taking a traditional video model that encodes frame-by-frame using a ViT into 16x16 patches, that's roughly 8,000 tokens per frame. Multiplying it out: 60fps × 60 seconds × 3600 frames × 8000 tokens = 28.8 million tokens for a one minute video! For context, most LLMs cap context windows at 128k tokens. As a workaround, many VLMs/World Models simply uniformly sample frames and/or limit the context window leading to either poor video understanding or exponentially compounding error over long horizons, since you can only keep a few frames as context.

Side note if you're interested: I did some work recently on improving long-context video understanding by "weaving" together short clips.

Now you must be wondering—what's the point in me talking about all this?

A world model like Genie 3, which can generate multiple minutes of a playable environment is far too large to ever run on consumer hardware. Similarly, this issue of exponentially growing compute requirements for long-context videos, makes it difficult to realize this dream of generative games without relying on the abundant GPU arsenal of frontier labs. Inspired by this problem, @njkumar's attempt at optimizing world models to play flappy bird in a web browser, and Ollin's demo of generating Pokemon using a neural net, I wanted to take a stab at creating a training recipe for world model-generated 2D games that could run on my Mac, without needing enterprise-grade GPUs for inference.

Model Architecture & Setup

In njkumar's blog post, he largely focuses on his efforts on flappy bird, a game without "too much visual diversity", as it allowed him to make heavy optimizations to enable generation on edge devices a little easier. My goal was slightly more ambitious: I wanted to generate games with greater visual complexity (e.g. Pokemon). I focus on two main architectures in this blog post: GameNGen and DIAMOND. As a baseline to compare architectures, I first focus on a simpler game (flappy bird) and then Pokemon. For flappy bird, I trained a PPO agent to play the game and then subsequently generated 30 episodes, each consisting of 800 frames with corresponding actions (0 - no flap, 1 - flap). For Pokemon, Ollin open-sourced the video data he collected along with text files with labeled actions which I graciously borrowed. Following my dataset format for flappy bird, I was able to write a script to generate ~20 episodes from 3 videos of gameplay, each consisting of 800 frames.

In GameNGen, frames are encoded into a compressed latent space using a Stable Diffusion 1.4's encoder. The latent is then passed through a U-Net denoiser, conditioned on a history of previous latent frames and player actions to predict the next frame. After spending some time reimplementing the architecture, I quickly realized that a) this architecture was far too large and slow for realtime gameplay on my Mac and b) the fidelity of the generated frames was quite low. The results on flappy bird can be seen as follows:

In DIAMOND, diffusion is done in a two-step process: a base U-Net denoiser which takes contextual low-resolution frames with corresponding actions to generate the next low-resolution frame and then a separate U-Net upsampler which outputs a scaled up version of this frame. In practice, this model had much higher visual fidelity and was roughly half the parameter count of GameNGen. The baseline results of DIAMOND on flappy bird can be seen here:

I generated this gameplay without playing the game live (i.e. I wrote a script to sample the model asynchronously). To generate 200 frames on my Mac, it took 5 minutes and 15 seconds (~0.63fps). Visually, the results using DIAMOND were great, but the model was far too large to be feasible for gameplay on consumer hardware.

Optimizations

I fiddled around with @njkumar's optimizations for flappy bird and while some of them worked, many didn't for higher-complexity games:

- Float16 Conversion: Casting to float16 reduces model size by approximately 50%, but while this worked for flappy bird, initial experiments with Pokemon yielded disappointing results.

- Conditioning Steps: By default, for higher quality games, DIAMOND uses 3 denoising steps in the denoiser and 10 denoising steps in the upsampler. In my experiments, I found that 2 denoising steps for the denoiser and 1 step for the upsampler were sufficient to maintain visual quality across different 2D games (we can get away with using smaller amounts of denoising steps since DIAMOND uses EDM as its diffusion formulation). However, I decided to go with the more expensive Heun ODE solver for the upsampler for a slight performance tradeoff due to poor visual fidelity when using Euler.

- Model Parameter Reductions: Prior to any reductions, the model had roughly 381,616,702 parameters (denoiser - ~330M, upsampler - ~50M)! I was able to reduce size for three components of the U-Nets (optimizations not made indicates tremendous loss in image quality/playability):

- Base Channels (↑ = better visual fidelity for complex games)

Denoiser: [128, 256, 512, 1024] → [64, 128, 256, 384], Upsampler: [64, 64, 128, 256] - Residual Blocks (↑ = deeper image processing)

Denoiser: [2, 2, 2, 2] → [1, 2, 2, 1], Upsampler: [2,2,2,2] - Conditioning Channels (↑ = richer temporal + action representation)

Denoiser: 2048, Upsampler: 2048 → 1024

From these changes, total parameter count went from ~330M to 104M (denoiser - ~73M, upsampler - 30M). Although this was enough to allow for inference on my Mac, I was only able to achieve a measly 2fps on Pokemon and 4fps with Flappy Bird.

- Base Channels (↑ = better visual fidelity for complex games)

- High-Compression Latent Diffusion: 2fps is still far too low for any sort of playability. Following njkumar's approach, I replaced the upsampler U-Net with a decoder and converted the denoiser to operate in latent space. Although this significantly increased FPS, the actual results were pretty disappointing on Pokemon:

My best hunch for why this method works for flappy bird and not Pokemon is simply because there are hundreds of sprites/environments contributing to greater visual complexity alongside a larger action space.

Modifying DIAMOND to support Variational Autoencoder (VAE)

Part of the strength of GameNGen's approach was the fact that it relied on this Encoder → Denoiser → Decoder architecture, but the autoencoder itself was a VAE. VAEs are trained with a KL divergence penalty that regularizes the latent space to be smooth and continuous, which is essential when diffusion models operate in that space. During denoising, latent vectors get perturbed by noise—and if the latent space has gaps or discontinuities (as vanilla autoencoders often produce), these perturbations can push latents into regions the decoder has never seen, causing visual artifacts. The VAE's regularization ensures that nearby points in latent space decode to similar images, so the diffusion process can move through the space without falling into 'dead zones' that produce garbage outputs.

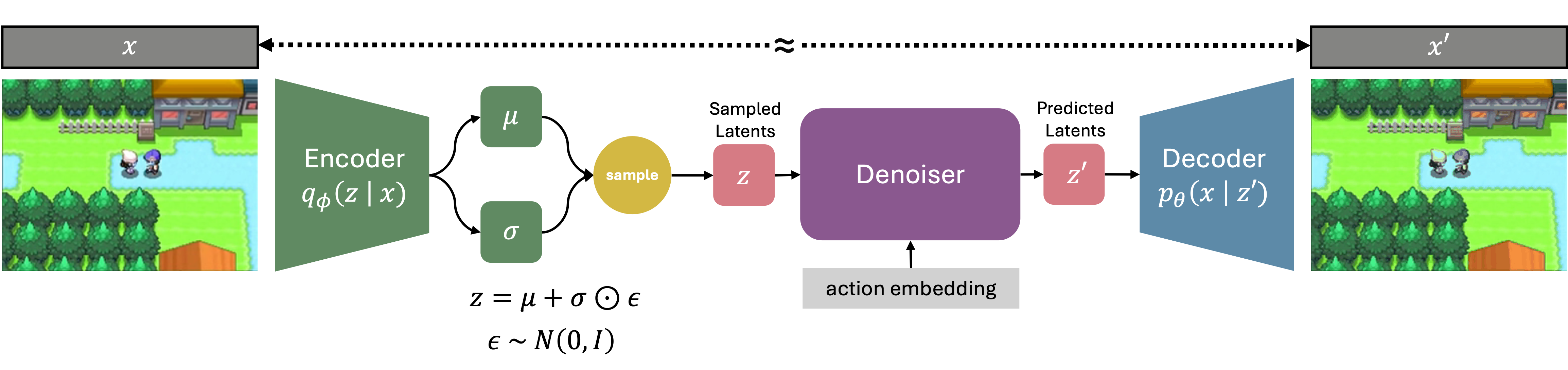

The primary disadvantage of using GameNGen is that the underlying VAE from Stable Diffusion 1.4 (alongside the U-Net) is far too large. Luckily, I was able to find an alternative approach called taesd, which shrinks the VAE from Stable Diffusion from roughly ~84M parameters to 2.4M. Overall, the modified DIAMOND architecture looks something like this:

The encoder compresses the original frame from 3×320×240 into a 4×40×30 latent which is passed into the denoiser which outputs predicted latents. These latents are then passed into the decoder which reconstructs the frame. The final parameter count for this version ended up being 75M parameters, a >5x reduction. You can see this model in action at the beginning of this blog post!

Conclusion & Future Work

After a few test-time optimizations I was able to achieve ~25fps on Flappy Bird, 15-18fps on Pokemon, and 20fps on Chrome's dino game (all results over long horizons).

Although I was able to achieve playable FPS on my Mac, the model is far too large to run in a web browser/mobile phone. Compared to Ollin's original approach, this version has much better stability longer-term and overall greater visual fidelity, but at a 250x increase in parameter count. With that in mind, in the future I'd like to explore either distilling the model to enable inference on even smaller devices, difficulty-adaptive compute (i.e. routing to appropriately-sized models depending on the complexity of the game), or style transfer via prompting (similar to Decart's recent demo).

Beyond world modeling for video games, I'm currently experimenting/excited about:

Sim2Real Transfer: If a world model truly learns physics and action-spaces from 2D platformers, it might be able to transfer its understanding of gravity, momentum, and collision that informs a robot's intuitive physics. Probing what world models actually learn—and whether it's causally meaningful—could bridge game simulation and embodied AI, especially considering the massive amounts of real-world data that must be collected to currently train robots. (General Intuition is the only company that's scaling up this "gaming" approach seriously at the moment)

Data Augmentation: A sufficiently capable world model could be responsible for recursively generating its own data based on its understanding of the environment, leading to a self-improving feedback loop. This bootstrapping may enable training on scenarios never seen in the original data, removing bottlenecks in a variety of applications including autonomous driving, video generation, and robotics.

Personalized medicine as world modeling: Our bodies are systems with state, dynamics, and responses to interventions. A personal world model trained on your continuous health data—sleep, heart rate, glucose, mood, etc.—could potentially model the "environment" that is your body. Suddenly, predicting responses to particular drugs or your proclivity to certain conditions adheres more closely to the practice of medicine (imagine simulating outcomes as opposed to just guessing them). This could bridge the gap between agents that are simply health advisors to ones capable of delivering specialist-level care.